The world’s largest cardiology congress hosted by the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) recently concluded in Amsterdam, bringing exciting news regarding the occlusion myocardial infarction (OMI) paradigm. Discover below the key insights from the updated guidelines for acute coronary syndromes (ACS).

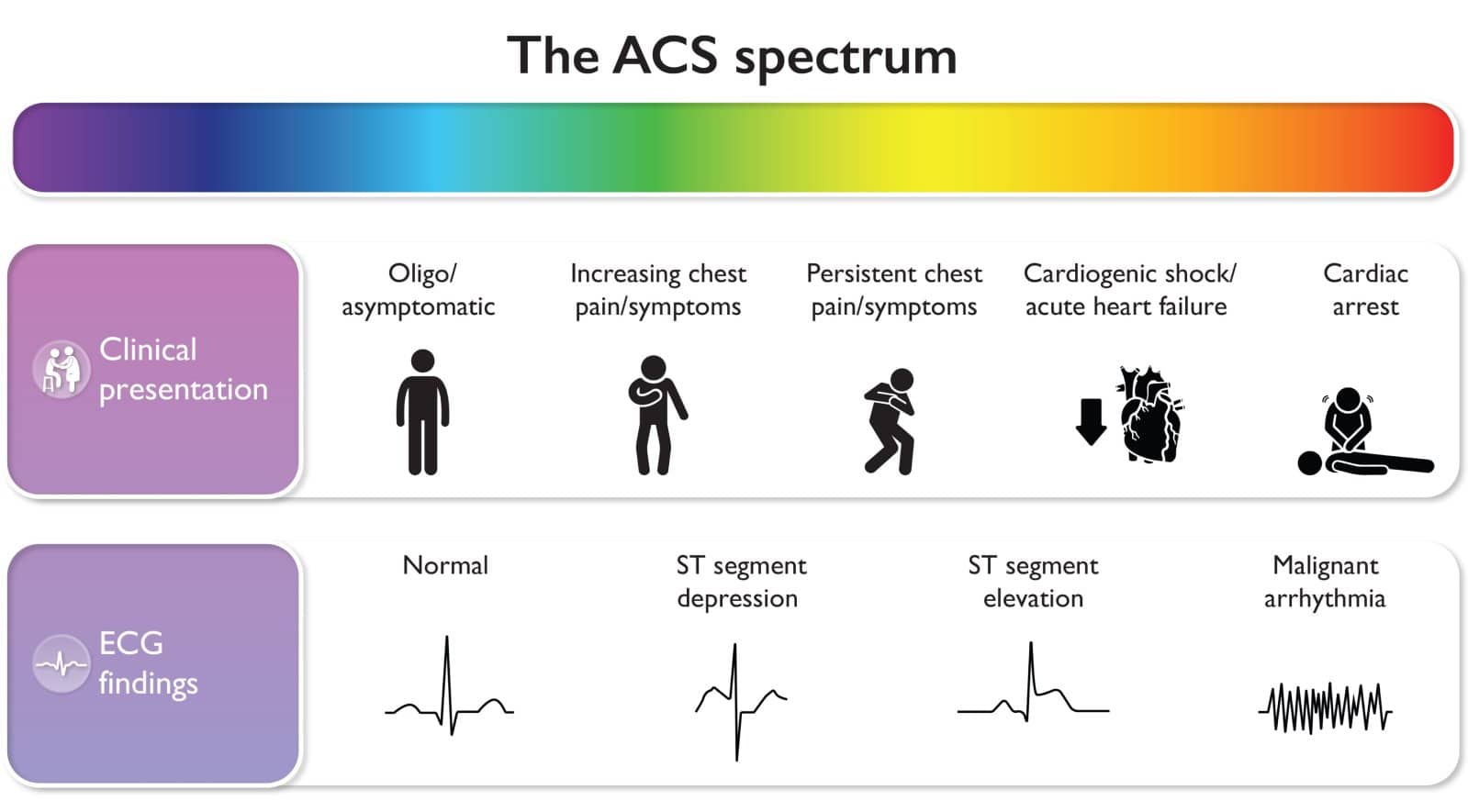

ACS is a spectrum

For the first time in history, an international cardiovascular society has merged clinical practice guidelines for ST-elevation (STE) acute coronary syndromes (ACS) with Non-STE (NSTE)-ACS, acknowledging that it is a spectrum of patients presenting with different clinical symptoms and dynamic ECG changes.

This mindset shift is a crucial initial move from the STEMI/NSTEMI dichotomy towards a diagnostic approach that better acknowledges the underlying pathology (acute coronary occlusion myocardial infarction [OMI]) in such patients. No other underlying pathology in medicine is named and defined dichotomously after the test used to initially screen for it, much less after one very inaccurate feature of the test (ST Elevation).

STEMI equivalents (although just in supplements)

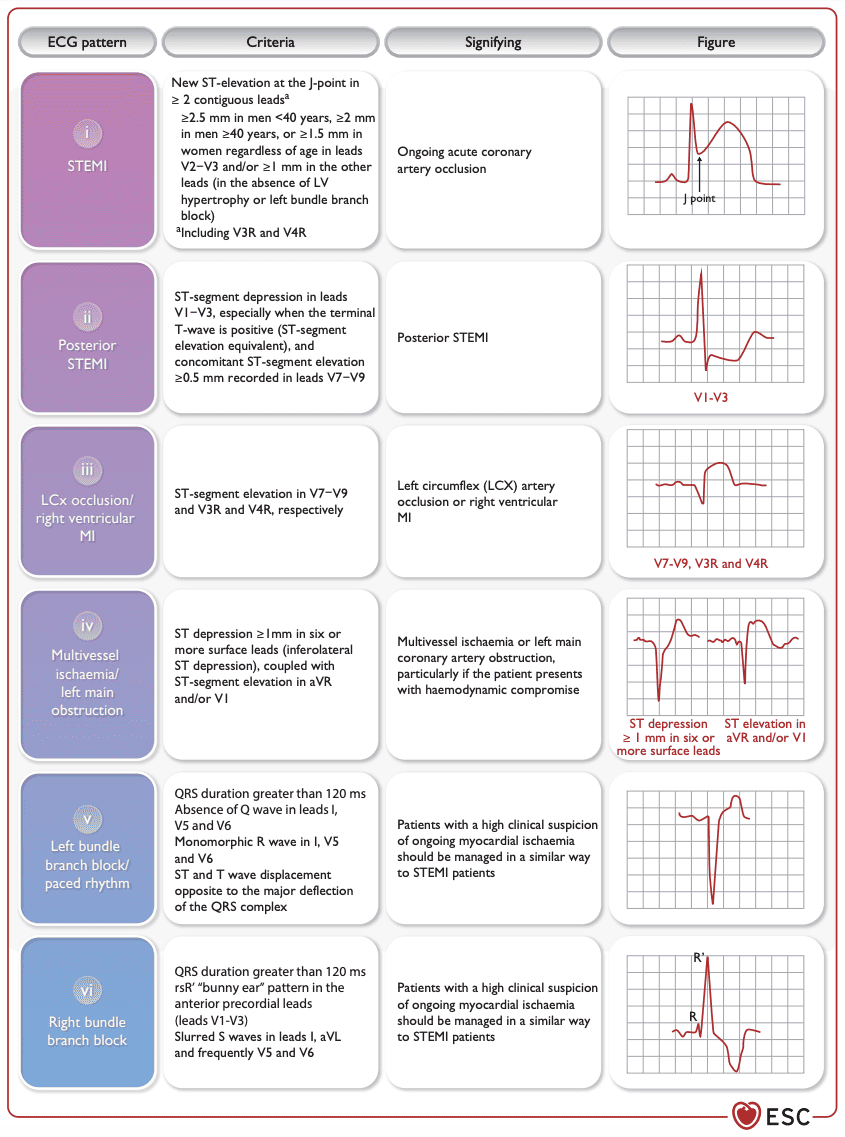

While the word STEMI is still used incorrectly as the main term for patients with ongoing acute coronary artery occlusion, the new guidelines clearly list a plethora of STEMI equivalents ECG patterns.

STEMI Equivalents: Navigating Hidden Indicators of Myocardial Infarction

“It is also important to recognize that while the most sensitive sign for ongoing acute coronary artery occlusion is ST-segment elevation, there are other ECG findings that can be suggestive of ongoing coronary artery occlusion (or severe ischaemia). If these findings are present, prompt triage for immediate reperfusion therapy is indicated (see Supplementary data online, Figure S2).“

In these patients, an immediate invasive primary reperfusion strategy is recommended with Class IA. Let’s hope the next guidelines will move these important patterns from supplementary information to being incorporated into the main body of the guidelines, reflecting their true significance.

Ongoing problems not addressed in the new guidelines

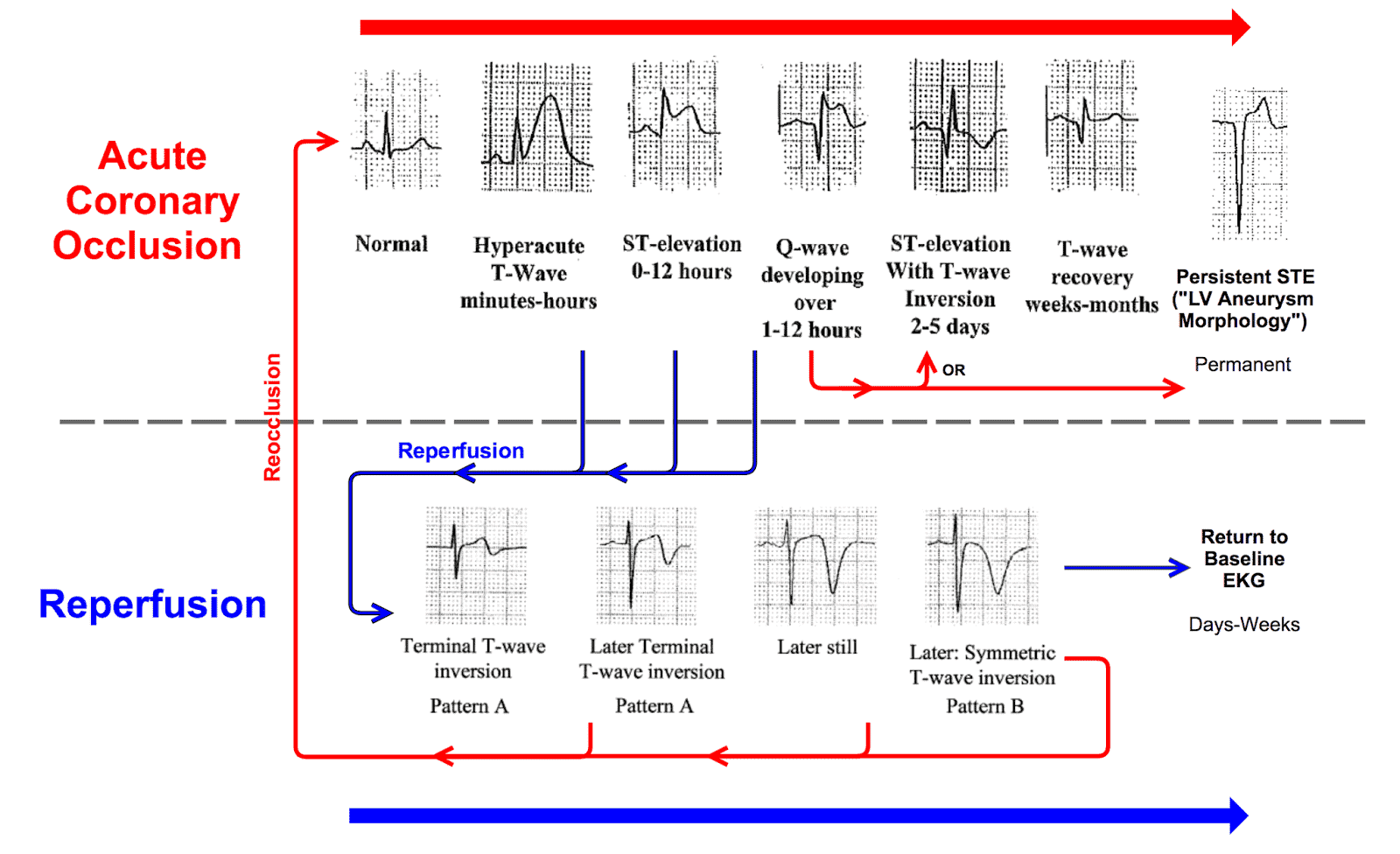

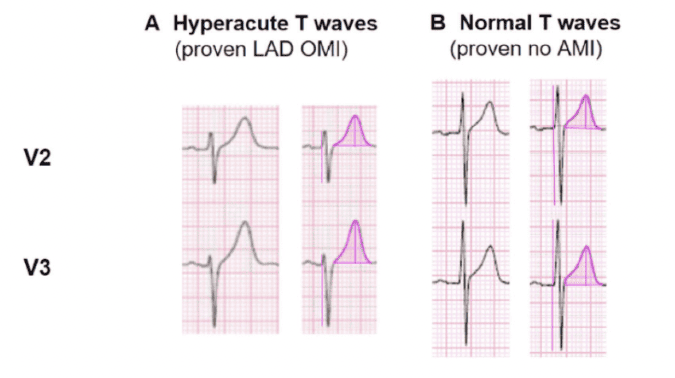

The guidelines acknowledge the dynamic nature of ACS, however interestingly, there is no differentiation between ECG patterns of patients with an active occlusion (i.e. de Winter) versus patients with reperfusion patterns (i.e. Wellens). Moreover, the only type of hyperacute T-wave that is listed is the “de Winter’s” pattern.

This is a hyperacute T-wave preceded by ST depression and is the rarest type of hyperacute T-wave; the vast majority of hyperacute T-waves do not involve a depressed ST takeoff. They are recognized by their area under the curve relative to the QRS size.¹

The guidelines do not mention additional sensitive and specific patterns for inferior OMI without using posterior leads, such as ST depression in aVL, or maximum in V1-V4.²

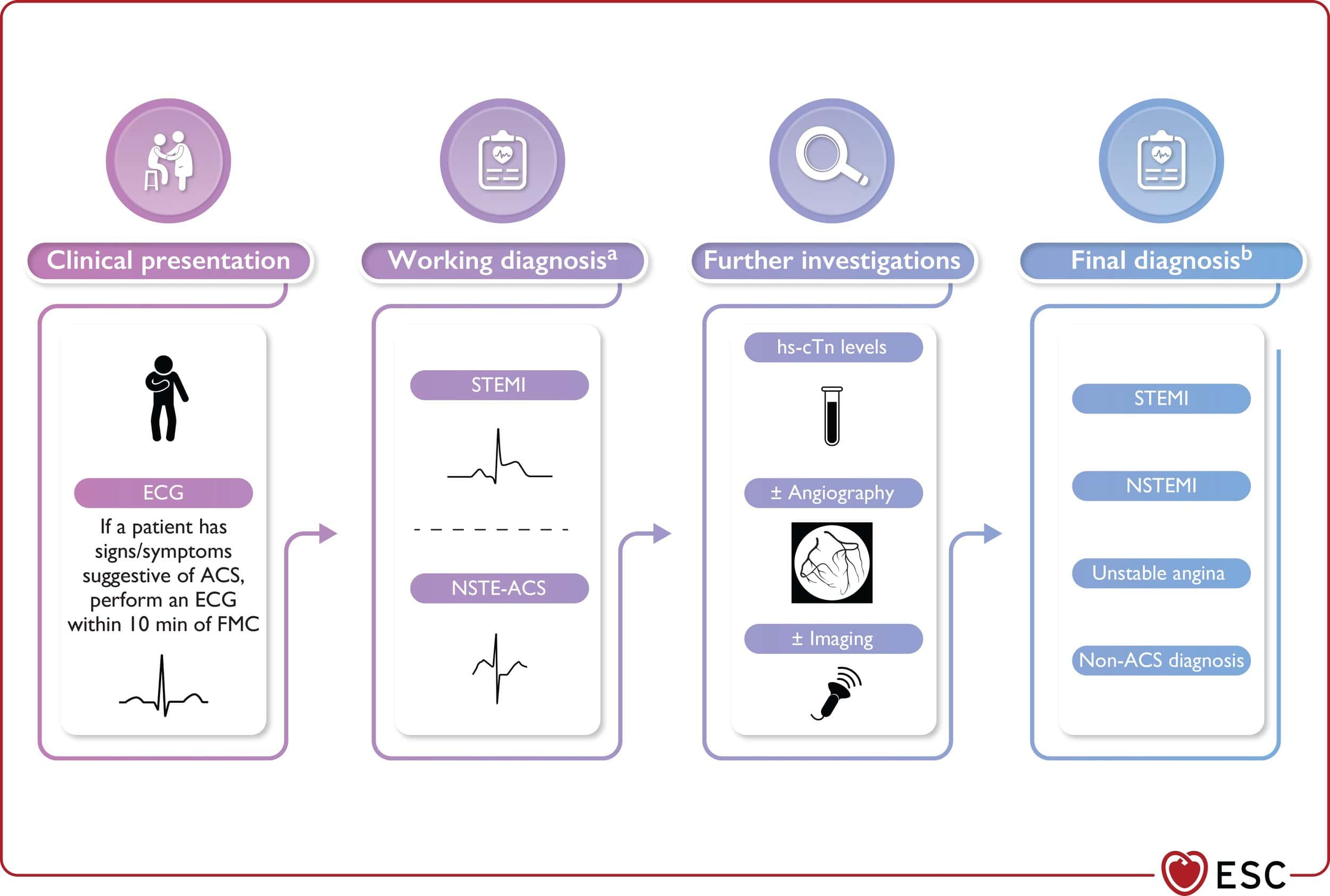

Concept of working and final diagnosis

The concept of a working and final diagnosis is introduced by the clinical practice guideline committee. The working diagnosis of STEMI vs. NSTE-ACS is determined based on the ECG at presentation, which is later adjusted after further investigations. However, there are still some significant drawbacks.

Although coronary angiography and further diagnostic testing establish the presence of an occlusive or flow-limiting lesion as a culprit for the present symptoms, the guidelines continue to give a “final diagnosis” based on inaccurate ECG terminology (ST-elevation and Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction).

This reinforces the logical fallacy of the STEMI vs. NSTEMI paradigm called the “No False Negative Paradox,” in which no NSTEMI patient can ever be recognized as a false negative for OMI, regardless of their underlying pathology or their benefit from emergent reperfusion.

As recently demonstrated by McLaren et al.³, final diagnoses typically highlight false-positive STEMI but never recognize false negative STEMI with proven acute coronary artery occlusion.

During the Question and Answer session, when asked why these terms are still used instead of more appropriate terms like “Occlusion MI” and “Non-Occlusion MI,” the answer provided was that the committee considered using the latter terms would be “too confusing” for physicians.

Great follow-up from the #ESC ACS guideline task force! They acknowledge the inaccuracy of referring to patients with an acutely occluded culprit artery as “STEMI” and were considering to change the terminology. Do you believe the world is ready for this change? pic.twitter.com/tbydxFnvIh — Robert Herman, MD (@RobertHermanMD) August 28, 2023

Conclusion

The revised ESC guidelines symbolize an initial step toward a more well-rounded perspective of ACS. This updated approach encapsulates the complexity of ACS patients and the myriad of ECG manifestations of acute coronary occlusion. However, improvements can still be made, particularly when it comes to using ECG-based terminology. We eagerly anticipate future developments that we hope will fully integrate the OMI paradigm for more precise diagnosis and enhanced patient care.

References

1. Druce I; McBeth J; van der Veer SN; Selby DA; Vidgen B; Georgatzis K; Hellman B; Lakshminarayana R; Chowdhury A; Schultz DM; Sanders C; Mamas MA; (2022, March). Digital health intervention for the management of chronic pain (CHOIR): a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Digital Health. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36872197/

2. Meyers HP; Bracey A; Lee D; Lichtenheld A; Li WJ; Singer DD; Rollins Z; Kane JA; Dodd KW; Meyers KE; Shroff GR; Singer AJ; Smith SW; (2021, December 7). Ischemic ST‐Segment Depression Maximal in V1–V4 (Versus V5–V6) of Any Amplitude Is Specific for Occlusion Myocardial Infarction (Versus Nonocclusive Ischemia). Journal of the American Heart Association. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9075358/

3. McLaren JTT; El-Baba M; Sivashanmugathas V; Meyers HP; Smith SW; Chartier LB; (2023, August 22). Missing occlusions: Quality gaps for ED patients with occlusion MI. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0735675723004382?via%3Dihub

Article reviewed by: H. Pendell Meyers, MD and Stephen W. Smith, MD